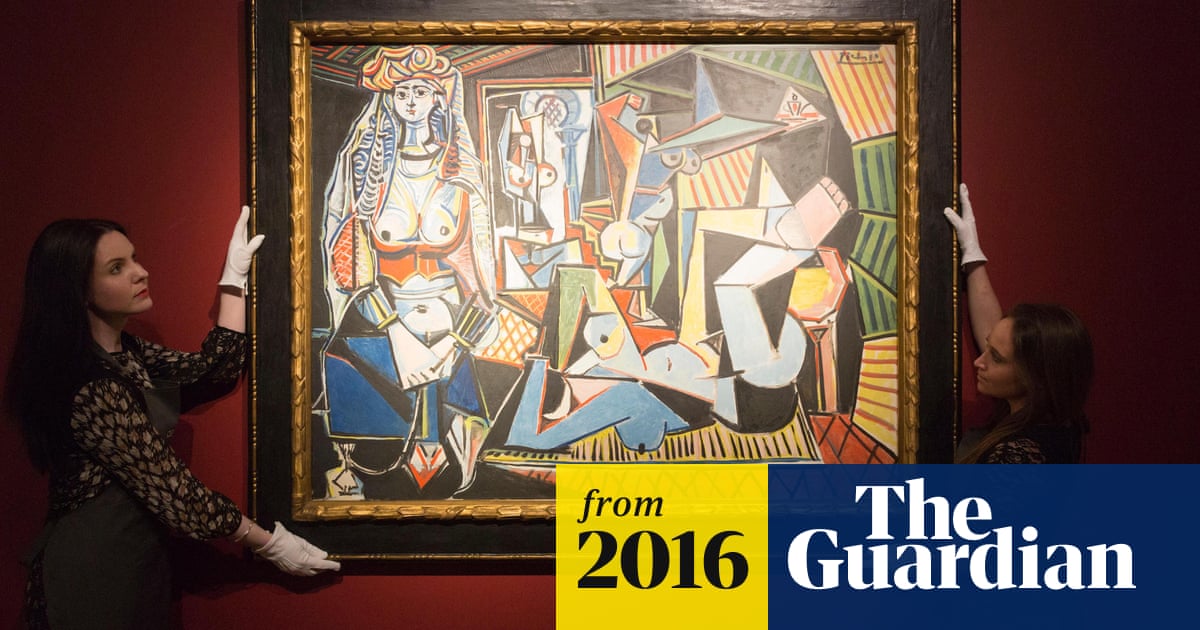

Lot 33 spun into view, hanging on a revolving panel. The brilliantly coloured Women of Algiers (version O), Pablo Picasso’s postwar masterpiece, was moments away from finding a new owner.

The year was 1997, and 2,000 people had assembled at the Manhattan salesroom of the Christie’s auction house. The collection of Victor and Sally Ganz, one of the most important caches of modern art in private hands, had drawn a capacity crowd. The audience grasped their bidding paddles, surrounded by smartly dressed assistants manning 60 specially installed telephone lines.

“Sixteen million,” the auctioneer announced. “Nineteen million … 20 million, 20 million dollars … 22 million … 27 million dollars? Twenty-eight million …”

When the hammer came down, the art world had changed forever. A London dealer, reportedly acting for a mystery Middle Eastern client, had paid $31.9m for a canvas acquired 40 years earlier for $7,000. The Ganz auction was regarded, even at the time, as a milestone. It marked the moment when art became a global commodity, an investment alternative to property and stock markets, at least for those at the top of the money tree.

“All of a sudden the game was afoot with the Ganz sale in a way that hadn’t happened before,” says Todd Levin, director of the Levin Art Group, a New York-based art advisory firm. “It was like a steroid injection to the market.”

What nobody in the audience at Christie’s on that frosty November evening realised was that the Women of Algiers, along with many of the other paintings in the auction, had already been sold by the Ganz family.

In a secret deal six months earlier, an offshore company whose bank account was controlled by the secretive billionaire currency trader Joe Lewis had bought all the most valuable works. On the same day, it had contracted to auction them at Christie’s, to be marketed as the Ganz collection.

It appeared Lewis had taken a $168m gamble that the art market was ready for liftoff. It would eventually pay off in multiple ways.

The story behind the auction that set a new record for the sale of a private collection can now be told for the first time.

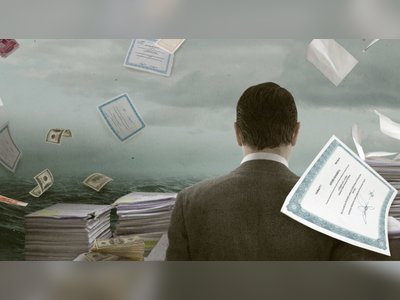

It has emerged from the Panama Papers, a trove of more than 11m documents obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists with the Guardian, the BBC and other partners.

The files may finally lay to rest rumours about how Christie’s snatched the Ganz commission from under the noses of rival auction houses. It is also a masterclass in the art of hedging by one of the world’s most successful financial speculators.

Lewis made his first fortune in catering, leaving school at 15 to help run his father’s business. After selling up he moved to the Bahamas in 1979 as a tax exile. It was from the Caribbean that he turned his millions into billions as a financial trader.

In 1992, he joined George Soros in a legendary bout of speculation that saw the British pound crash out of the European exchange rate mechanism. The event became known as Black Wednesday, and while Soros took the flak for profiting from a crisis, becoming a household name in the process, Lewis is said to have quietly walked away with a bigger slice of the winnings.

“I really feel that if one is successful, one of the rewards of your success is the quiet enjoyment of it,” he once told an interviewer. “Being on the front page of newspapers doesn’t allow that.”

While the man may be low-key, his investments are anything but. He backed the Planet Hollywood restaurant chain and is best known these days as the owner of London’s Tottenham Hotspur football club. In Scotland, he is remembered for pumping £40m into Rangers football club in Glasgow.

The files leaked from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca are full of offshore companies Lewis has incorporated to hold these investments. Many of them have as a shareholder the Bahamas-registered Aviva Holdings Ltd, incorporated in 1993 and named after a series of enormous yachts that have served as his floating offices-cum-art galleries.

Lewis is said to spend months onboard, travelling the world on business. He takes his prized collection with him; it contains works by Lucian Freud, Gustav Klimt, Paul Cézanne and Picasso.

The road to the auction

The Ganzs, who owned a costume jewellery business, began collecting after the second world war. As well as Picasso, they focused on Frank Stella, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Eva Hesse, all pioneers of the abstract style. They spent 50 years and $2m assembling the pieces. After the couple died, inheritance taxes became due and their children decided to sell the pictures that had adorned the childhood home.

During the fortnight preceding the sale, 25,000 visitors had filed through Christie’s, eager to catch a glimpse of the paintings before they disappeared once more into private hands. The auction itself was a high-society event, with the cosmetics king Leonard Lauder and William H Gates, father of the Microsoft founder Bill Gates, squeezing into the packed halls.

The Christie’s auction in 1997. Photograph: Stan Honda/AFP/Getty Images

Even before the bidders filed in, Christie’s knew the sale had been a success. This was because in May 1997, a corporation based on Niue – a tiny island in the South Pacific – had already handed over millions of dollars to buy the works.

Simsbury International Corporation, first registered in April 1997 and dissolved in December 1999, appears to have been created solely for the Ganz auction. Its registered agent was Mossack Fonseca.

Employees of the law firm served as Simsbury’s nominee directors, stand-ins who controlled the company on paper but who exercised no real authority over its activities.

According to the documents, the identity of the person who controlled Simsbury is revealed by minutes of a meeting of the directors from 1997, in which he was given signing rights over the company’s bank account. These state: “The company shall open a bank account with Republic National Bank of New York [Suisse] SA … and by means of this resolution grants power of attorney to Mr Joseph Charles Lewis … to open and manage the company’s bank account .”

Lewis did not respond to requests for comment.

Among the other papers is an agreement struck on 2 May 1997 between Simsbury and Spink & Son, a London auction house that had been acquired by Christie’s a few years earlier.

In it, Simsbury undertakes to buy from Spink more than 100 of the Ganz paintings, including the three most valuable Picassos in the auction.

In a second contract, also dated 2 May 1997, Simsbury agrees to place the paintings it has bought into the Christie’s auction. It states: “Spink has sold the consignor, and the consignor has purchased from Spink, certain paintings identified in the sale agreement ... The consignor wishes to consign the paintings for sale at auction and has agreed to enter into this agreement for that purpose.”

A further clause makes it clear that Simsbury’s owner would not be allowed to bid on the night.

Should the final bid prices on all sold paintings have exceeded $168m, the documents suggest Simsbury and Spink would split the difference. The event broke all previous records for a private collection, fetching $206m.

Experts who have seen the papers believe Spink was acting as a broker – buying from the Ganz family and selling on to Simsbury. A representative from the Ganz family declined to comment. There is no suggestion of illegality about any of the arrangements.

Christie’s would have been in fierce competition with rivals, including Sotheby’s, to win the prized commission. Offering to buy the work in advance of the auction for such a large sum may have helped swing the deal.

Christie’s had no comment. It is understood the auctioneer believes the necessary disclosures were made at the time and that the matter is past because the events took place nearly 20 years ago under previous management and ownership.

An art market revolution

Multimillion-dollar auction financing is now commonplace at the highest end of the art market. These days, however, it usually takes a different form: typically that of guarantees, where an independent party underwrites the sale and goes home with any work that does not find a buyer at the minimum price.

In 1997, such arrangements were almost unheard of, though there was nothing illegal about them.

The Ganz catalogue simply stated: “Christie’s has a direct financial interest in all property in this sale.”

A report in the investment magazine Barron’s, published before the auction, pointed out: “Exactly what this means, Christie’s isn’t saying, but one can safely bet that the firm is bearing a substantial monetary risk on the outcome.”

In fact, it appeared much of the monetary risk was being taken by Simsbury. And Lewis had an interest at both ends of the transaction: the currency trader was at the time the single largest shareholder in Christie’s. The company is privately owned now, but then its shares were listed on the London Stock Exchange, and Lewis had started buying them in 1994, through a Mayfair broker.

Within two years he had reached 28.7%, just below the 30% mark at which investors must make an offer for the whole company.

Christie’s enjoyed a bumper year in 1997. As well as the Ganz collection, it landed a series of prestigious commissions, snatching the best pieces from under the noses of its competitors. Sotheby’s was left trailing as its rival raked in about $2bn in sales.

As art prices surged, so did Christie’s shares. In February 1998, the investment banking firm SBC Warburg Dillon Read offered to take Christie’s private, in a consortium that included Lewis. SBC’s argument was that being a private company would allow Christie’s greater flexibility in finding backers to underwrite its auctions.

Its bid was rejected as too low, but the noise attracted another buyer. By May 1998, the French retailer François Pinault had bought Lewis’s stake for an estimated £200m, before snapping up the rest of the stock for just under 400p a share.

Lewis, who bought his holding for about £100m, had doubled his money. Simsbury’s hidden owner appears to have used his financial clout to help Christie’s win new business. In the process, he had made a killing on his public investment in the company’s shares.

Whether he took home any of the Ganz collection is not known. Simsbury’s contract had placed individual high-value bets on the most impressive Picassos, but they all found buyers.

Lewis told a reporter for Fortune magazine recently: “Being a trader means that you are wrong at the very least three times out of 10, and that is very hard.”

At Christie’s, he seems to have achieved a better hit rate. The Dream, a study of Picasso’s young mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter, was bought by Simsbury for $45m and sold in the Ganz auction for $48.5m. Lauder paid $25m for Femme en Chemise – which he eventually bequeathed to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. It had been bought by Simsbury for $20m, according to the documents, and advertised in the auction catalogue for $15m to $20m.

The masterpiece disappeared from public view for the next 18 years. It is said to have been kept at a London house belonging to a Saudi collector. In May last year, the canvas returned to Christie’s, where history repeated itself, at a sale fittingly titled Looking Forward to the Past.

Women of Algiers (version O) now belongs to another undeclared buyer who paid $160m, setting a new record for the most expensive artwork sold at auction. Confirmation, if any were needed, that the latest lull in the global economy has done nothing to slow the inexorable rise of the super-rich.