Coutts, the taxpayer-owned bank, provided offshore services to controversial clients including a member of the Brunei royal family accused of stealing billions from his own country, and a banker charged with assisting the sons of Egypt’s deposed president, Hosni Mubarak, in financial crime.

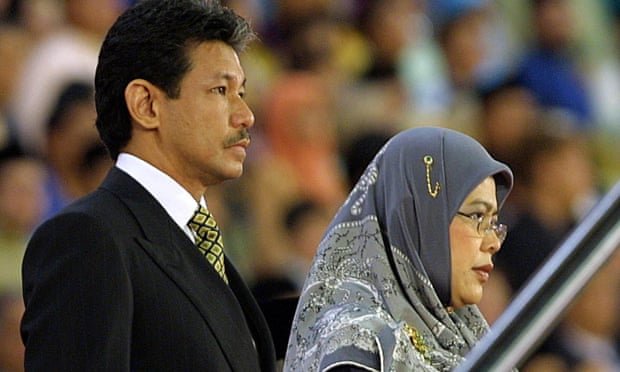

Known as the Queen’s bank after its most famous customer, Coutts is revealed to have managed secretive tax haven structures for the Sultan of Brunei’s younger brother, Prince Jefri Bolkiah, and the investment banker Hassan Heikal.

The information was uncovered in the Panama Papers, a database of 11.5m documents leaked from the archives of the offshore law firm Mossack Fonseca.

Emails between Coutts and Mossack show the law firm regarded these individuals as presenting a high risk under criteria designed to combat money laundering: Jefri was ordered by a UK court to repay an estimated $15bn taken from the Brunei sovereign wealth fund, which he chaired; Heikal was charged in 2012 and is awaiting trial for facilitating insider trading, which he denies.

Both were clients of Coutts & Co Trustees in Jersey. Their offshore companies were active until at least the end of 2015. The bank would not confirm whether they remained on its books, saying it did not comment on individual cases.

The revelations raise new concerns about controls at Coutts, which was fined just under £9m four years ago for major failures in its checks on high risk customers, including those with political connections. Regulators said at the time these led to an “unacceptable risk of Coutts handling the proceeds of crime”.

While it is entirely legal to offer banking services to what are known as politically exposed persons (PEP) – politicians, state officials and their families and associates – these individuals must be subject to enhanced checks, in particular on their source of funds.

Between 1986 and 1998, Jefri served as finance minister of the oil-rich state and chairman of its sovereign wealth fund. In a breathtaking spending spree, cash from the Brunei Investment Agency was funnelled into more than 500 properties around the world. Jefri amassed thousands of luxury cars, antique paintings by Renoir, Manet and Degas, five boats, and nine aircraft including a private Boeing 747 reportedly customised to carry polo ponies.

In a settlement agreed in 2000, Jefri undertook to return the money to Brunei. Years of litigation in various jurisdictions followed, with Jefri challenging the repayment agreement, saying he had only acted on his brother’s orders, but the British courts upheld it.

The legal battles ended in 2014 when Brunei accepted that the prince had honoured the original settlement.

Records show Jefri remained a Coutts client throughout this period. Mossack Fonseca learned only last year that it was acting as registered agent for two British Virgin Islands companies of which Jefri was the ultimate beneficiary. Crescent Invest & Trade was incorporated in 1998, the year the prince resigned as finance minister. Taurus Estates Limited was set up the following year.

Crescent had held shares but became dormant, while Taurus held a bank account with Coutts Zurich, a commercial property and seven residential apartments in London, Coutts explained in emails to Mossack Fonseca. The UK property register shows Taurus owns six floors of a building in London’s exclusive Dover Street, a stone’s throw from the Ritz hotel, acquired in 1999. It is in turn owned by a trust, called PJ Settlement.

Jefri’s involvement was effectively masked, because Coutts and its sister companies supplied nominee directors and shareholders for Taurus and Crescent, and trustees to PJ Settlement. This is a common practice where offshore companies are concerned and is not illegal.

When Mossack Fonseca learned of the prince’s involvement, it immediately resigned as agent, telling Coutts his companies “present a high risk to us”.

“The proceedings between the Brunei Investment Agency and HRH Prince Jefri Bolkiah came to an end in 2014 when the Investment Agency acknowledged that he had complied with all the terms of the settlement agreement made in 2000,” said Jefri’s lawyer, David Sandy.

Since 2008, BVI law has required company agents to supply information on owners to regulators “without delay”. In order to comply, Mossack began a housekeeping exercise with Coutts & Co Trustees in June 2014, writing to ask for a list of all its Jersey PEP clients with shell companies. The firm also wanted supporting information such as passport scans and proof of address.

The email chain shows that thanks to delays on both sides, and a set of couriered documents that went astray, it took until September last year – a full 15 months after the initial request – for all the required information to be supplied.

Coutts declared 11 PEP clients, including Hassan Heikal. Until 2013, he was co-chief executive of EFG-Hermes, one of the Arab world’s largest investment banks. Heikal is currently awaiting trial alongside Mubarak’s sons Gamal and Alaa. He is banned from leaving Egypt.

In May 2012, following Mubarak’s overthrow, his sons were indicted for insider dealing in a case involving EFG-Hermes. Heikal, along with two colleagues, was named as a co-defendant, accused of “assisting in committing the crime of profiting”.

Through its trusts division in Jersey, the channel islands tax haven, Coutts managed two BVI companies for Heikal – Mmoni Investments Limited and Eydon Limited, both of which had bank accounts in London in their name, at least one of them with Coutts. As with Prince Jefri’s shell companies, Coutts also provided nominees to hold the shares and act as directors.

After Mossack raised concerns about Heikal in 2015, Coutts replied: “We are aware of the adverse information and are monitoring the situation, details of which are available in the public domain. The group [Coutts] is in regular contact with the client [Heikal] and we are comfortable at the present time to continue to provide our services.”

Heikal, who resigned as co-chief executive of EFG-Hermes in October 2013, denies the charges against him. He is not accused of personally profiting from the alleged scheme. He forwarded a statement released in 2012 by EFG-Hermes, which asserted that its co-chief executives had “no personal dealings, interests or benefits in any transactions related to the trading on Al-Watany Bank of Egypt’s shares”.

The Jersey trustees business was put up for sale by Coutts in October, and senior management of Coutts & Co Jersey are negotiating to buy it. The bank said: “We take our responsibilities under anti-money laundering (AML) and anti-corruption regulations extremely seriously and have policies in place to ensure compliance with the regulations in the jurisdictions where we operate. Our guidelines on working with politically exposed individuals are in line with AML regulations and we take a proactive approach to these issues, which impact all banks.”

Eleanor Nichol, campaign leader at the anti-corruption group Global Witness, said: “It is startling that Mossack Fonseca – of all firms – immediately raised a red flag on its relationship with Prince Jefri but Coutts appeared comfortable with the level of risk. This is the Queen’s bank, after all – the case raises questions as to whether UK banks are applying high enough standards for screening their customers before they take their money.”

Additional reporting by Mona Mahmoud and Juliette Garside